Bargueño, the Spanish cabinet for all your secrets

It looks like a jewel box and it works like a security safe. Jealousy guarded and yet seductive in its ornamentation, the bargueño, Spain’s most singular contribution to Renaissance furniture, is a paradox in a box.

The bargueño is emblematic of a character that is at once reserved and extravagant. Reserved because, from the outside, this cabinet looks rather modest. The fall front fastens up to create a perfectly ordinary chest. However, once open, the breath of the artwork and sheer number of drawers and doors enthralls the viewer.

Imagine the feeling of trust and conspiracy one bestows upon the friend who is allowed to see this unveiling and then, the things within?

Commonly used from the 16th and 17th centuries, the bargueño was a portable writing cabinet employed by bureaucrats. In style, it is similar to the 16th century French bureau brisé with its foldable top that turns into a writing table.

Though there are innumerable variations in form and decoration, we may distinguish a few broad categories of bargueño. Technically speaking, any bargueño was understood to be a set of two pieces of furniture, the upper writing cabinet and its lower support.

The bargueño de pie de puente, literally the “footbridge bargueño,” stands on a pair of sturdy, carved legs joined by a cross beam. The bargueño de taquillón sits a chest of drawers, usually containing four compartments of equal size. Most bargueños were made of walnut wood.

A 16th century bargueño de pie de puente, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Beyond these structural differences, we may find broad regional styles. The bargueño salmantino (of Salamanca) looks like a church altar, and may feature lions in its iconography. Andalusian bargueños reflect a strong Mudéjar influence while the bargueño frailero, destined for monasteries, showed great restraint in its level of ornamentation.

Given the Spanish Empire’s reach throughout the 17th century and trade relations in Europe, we also find similar furniture like this Flemish cabinet. Dutch painters decorated the façades with the same level of skill previously reserved for large oil paintings.

This Peruvian mini-bargueño copies the formal structure of the traditional Spanish bargueño faithfully and, though it lacks handles, its small size, 48 cm wide, made it easy to transport.

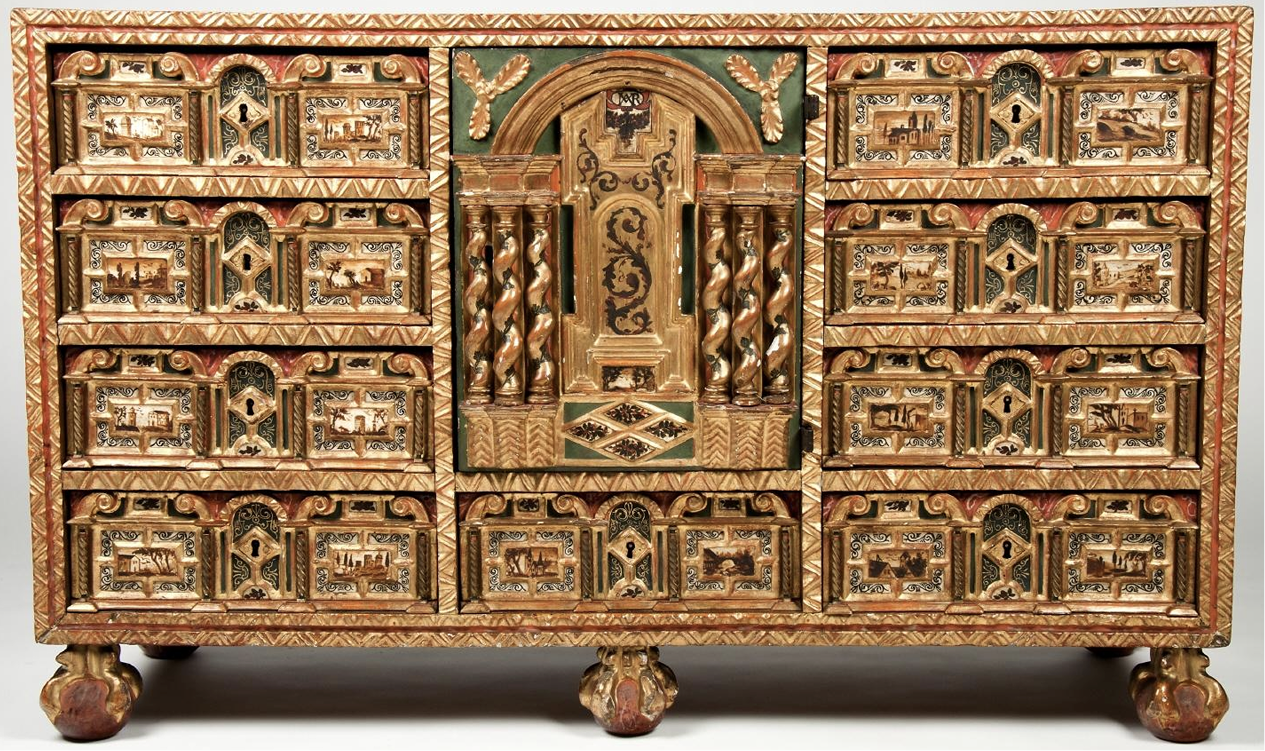

A Bargueño de taquillón sits a chest of drawers, usually containing four compartments of equal sizes, Museo Sorolla.

The bargueño as symbol of power and efficiency

A powerful symbol of European erudition in the age of the printing press, the bargueño travelled to the Americas, where it became a powerful symbol of Spanish culture and authority. The new Spanish colonies required a great web of administrators, governors and other bureaucrats who in turn needed the right tools to capture, categorize and store all that they could learn about these new lands. In this context, the bargueño, which could have become a mere “cabinet of curiosities” where the householder kept a few valuables and items of sentimental value, became a technology to organize the massive amount of information captured through writings, letters, legal documents, botanic illustrations or maps.

Myriad intricate interior drawers provided safekeeping for jewels and other small valuables including billetes, small scraps of paper containing secret messages that had to be hand-delivered and without the aid of intermediaries.

In the era of colonial expansion, information was the next best thing to gold.

In the 1998 film, the Mask of Zorro, the Mexican governor Don Rafael Montero hides the map for the gold mines on his Alta California estate in his bargueño. Given that the film is set in the 19th century, it’s plausible for him to have a treasured antique bargueño at his stately mansion.

A 19th century bargueño done in walnut wood with polychrome decoration and gilding, Susana Vicente Galende.

The origin of the Spanish bargueño cabinet

Art historian Tamara García Cuiñas reports that there is no mention of a “bargueño” in any documents from the XV, XVI, XVII or XVIII centuries. The first recording of the name “bargueño” is an anecdotal note the curator Juan Facundo Riaño included in his 1872 catalog for the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum. He describes the bargueño as a “cabinet: walnut wood, in two parts, the upper with falling front, ornament with pierced iron plates, the interior containing a central door of architectural design, concealing nine inner drawers and twelve other drawers, the fronts of which are arcaded and decorated with diaper ornament in ivory, panelled in Moresque style, coloured in gilt, after the manner known as “Vargueño,” from the village of Vargas, in the province of Toledo.”

Unfortunately, historians have found scant evidence of a strong carpentry industry in the area in the 16th century when this style of cabinet emerged. But, the name stuck because it helped academics and antique dealers distinguish this chest-on-stand from other escritorios, writing desks of the same period.

An inventory of Spanish furniture from the Middle Ages and Renaissance suggest that this writing desk is the meeting of two lineages: the Moorish escribanía, a compact document safe commonly used in the Nasrid kingdom of Granada in the 14th century, and Catalonia’s traditional dowry chest.

Antique bargueños are a rare find and even rarer are the artisans who can still make this singular piece of furniture. Though they fell out of fashion in the 18th century, passionate collectors either commissioned new pieces in the old style or patiently searched for well-preserved antiques.

The Sorolla Museum in Madrid, housed in what was the painter’s actual home, has a small collection of his bargueños on display.

Looking for a custom piece or Spanish antiques? Please get in touch for specific sourcing requests.